"You Couldn't Be Anything Else": Gay Subtext in Richard Stark's Parker

A decidedly uninterested Parker in the Italian edition of The Rare Coin Score (1967)/Parker: Rapina A Sangue Freddo (1968).

"My partner," he said.

"In the store?"

"Yes. Everywhere."

- A Jade in Aries (1970)

According to an autobiographical little tidbit on his website, the Stonewall uprising broke out while Donald Westlake was working on A Jade in Aries – the fourth novel featuring P.I. Mitch Tobin, and his investigation into the wrongful death of a gay man. It was an auspicious coincidence, but LGBT themes weren't uncommon in Westlake's work; he'd had his debut during the 'sleaze' novels craze of the 1950s, writing lesbian pulp fiction along would-be big names like Patricia Highsmith and Marijane Meaker. Still, Jade is often thought of as something of an outlier; being as it is a deep dive into the gay culture of the era with a sympathetic and layered portrayal of gay characters that's practically unheard of in the annals of mainstream crime fiction.

Donald Westlake was, of course, no stranger to crime fiction. At that very same time, he was still operating under the pen name of Richard Stark and writing the books he would be best remembered for: the Parker series. That was the true outlier in a career singularly concerned with LGBT themes – a gaycoded protagonist.

Gay characters are unexpectedly prevalent in the Parker novels; initially referred to in passing with derogatory terms ("a latent fag with big hips"1 in The Hunter), eventually heavily alluded to (the young man with the bare midriff and "rouge on his cheeks"2 in The Man with The Getaway Face, Bob Negli and Arnie Feccio whose "life together was a series of compromises and adjustments"3 in The Seventh, Steuber in The Handle who was "Baron's whole world and equally so was Baron the world for Stueber"4, Terry Atkins' mistaken impression of Billy Lebatard in The Rare Coin Score when he wonders if "Lebatard might after all be homosexual and had picked up – or been picked up – by an older man of the same type"5, Ellen Fusco's ex-boyfriend in The Green Eagle Score who had "deep-seated hidden fears that he was a homosexual"6), ultimately becoming layered supporting characters towards the end of the original series (Paul Brock and Matt Rosenstein in The Sour Lemon Score, Leon Griffith and Jacques Renard in Plunder Squad).

Stark – or Westlake, if you prefer – was clearly following societal change but if the times were a-changing, so was Parker as a character. As the books went on, Stark's stance became clear.

Parker has often been called a static character, as if he existed exclusively in the ‘rough, macho’ world perceived by a straight male audience unwilling to look beyond the first book, but what has often been ignored in any critical engagement with Stark's novels is the gradual thawing of Parker in the presence of his best friend and partner, flamboyant actor Alan Grofield. Parker's character development is subtle at first, then monumental. Butcher's Moon, the final book in the series, follows the exact same plot as the initial trilogy (The Hunter - The Man with The Getaway Face - The Outfit) but Parker's motivation is no longer money, it's love.

In The Outfit, we're told "possessions tie a man down and friendships blind him. Parker owned nothing, the men he knew were just that, the men he knew, not his friends [...]"7. Parker is cold, methodical, blunt, taciturn, repeatedly said to dislike small talk and most kinds of 'needless' social interaction. When he runs into Grofield in his introductory chapter in The Score, he greets him like an old friend. The discrepancy is immediately apparent, and only grows throughout their appearances together. In that very same book, Parker comes across as betrayed when Grofield brings a girl along after the heist; he tries to drive her away by listing all of Grofield's faults – the most Parker's spoken by that point in the series. He knows every side of Grofield, and still thinks of him as a "good man"8. It's a familiarity, an intimacy, Parker never displays with any other character.

Two books later, in The Handle, Parker goes out of his way to save Grofield's life. Where he's usually averse to touch, he lets Grofield sleep on his shoulder. It's here that a pattern emerges, Parker's willingness to come to the rescue is unique to their dynamic, their relationship singular in Parker's life. The final chapter of the book highlights the strangeness – the novelty – of Parker's feelings in a homoerotically-charged scene, where he justifies his actions as "we were working together"9 and it's an explanation Grofield accepts with an air of something knowing about him; as if it's become clear to him, too, that Parker never has done this before.

Parker and Grofield’s meaningful goodbye in The Handle.

Parker's brief flings with women are portrayed as constant but unsatisfying, and take an unusual turn after The Handle. In The Rare Coin Score, sex is compared to a fight Parker gets into but it's only the latter he's said to prolong "for the pleasure of it"10, ranking a homosocial setting above heterosexual entanglements. In Stark's world, heterosexual sex is never equated with pleasure where Parker is concerned – it's functional, a much-needed release of adrenaline; which makes its disappearance in the latter half of the books all that more notable. Rare Coin also introduces Claire Carroll, Parker's would-be long-term companion, but their relationship is cold and dispassionate and each seems to serve a purpose for the other. Claire's role in Parker's life reads as a consequence of a piece of advice from Grofield in the previous book ("Without a woman on your arm, you'd look like forty kinds of trouble."11), rather than the result of any genuine feelings.

The key to Parker's relationship with women lies in The Sour Lemon Score. A year before A Jade in Aries, that had been Westlake's first foray into a lengthy exploration of LGBT themes, and it still remains a striking one. Paul Brock and Matt Rosenstein – the gay couple at the center of this tale – are deeply compelling, deeply complex characters. Rosenstein is deep in the closet and drowning under internalized homophobia but he's also presented as a dark mirror of Parker, the man he could've been had he been any less self-aware. His repeated encounters with women, identical to Parker’s, are summarily presented thus: "he'd taken sex the way he'd taken money, where he could get it and any way he could get his hands on it. It had never pleased him as much as money, but it had never occurred to him there might be any reason for that [...]. When he got a shot at a woman he still took it and it still wasn't very good, but he was still straight."12

Yet Rosenstein is irrevocably and explicitly gay, simply acting out of self-hatred. When his boyfriend, Paul Brock, first meets Parker, he says that Parker reminds him of Rosenstein and that he "couldn't be anything else"13. The subtext nearly becomes text then, double-meanings brought to the surface. If the dawning realization of his sexuality had nearly broken Rosenstein though, it appears to free Parker and allow him to grow as a person. For the remainder of the series, Parker is more aware of his emotions and no longer reacting negatively to what he considers 'irrational' feelings; not softened but at ease as if he'd taken to heart what he'd seen in Sour Lemon. His personal life is bare then, Deadly Edge confirms Claire sees their arrangement as a practicality serving them both well, and in Plunder Squad Parker is actively repulsed by a woman making advances.

Parker & Paul Brock’s conversation in The Sour Lemon Score.

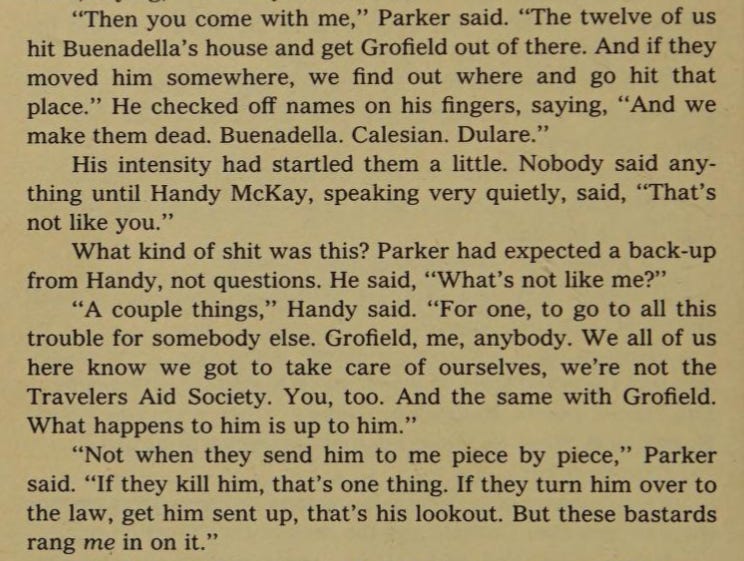

It all comes to a head in Butcher's Moon. When Grofield is shot and kidnapped, it's presented as the only way to hurt Parker. The homoeroticism and subtext implicit to their relationship is on full display during Parker's subsequent quest for revenge. His distress at having received one of Grofield's severed fingers, which he holds onto, is brought into question in the text by one of Parker's closest associates. When Handy McKay claims such sentiment is unlike Parker, Parker decides he doesn't care and launches into a speech about the necessity of rescuing Grofield – another act so entirely unlike him, man of few words that we know him to be, that the fellow heisters present are said to be startled by his intensity. It's an earlier scene that encompasses all that Grofield means to Parker though. In a mob boss' den, surrounded by enemies he's now practically pleading with for help, Parker says, "you're not leaving my partner there."14

Parker’s speech in Butcher’s Moon, the most he speaks in the entire series.

That's how Westlake comes back to a sentiment first expressed four years prior in A Jade In Aries. He proposes that Grofield is, indeed, Parker's partner everywhere. In fact, it's Westlake's nonfiction writing that not only encourages this reading but implies intent. In discussing Raymond Chandler's work in a 1984 essay on genre featured in The Getaway Car, Westlake proposes that "homosexual content was one of the elements [...] that gave hardboiled stories their texture and fascination, and make them still alive today, more than forty years after they began."15 Looking at Philip Marlowe and Terry Lennox in The Long Goodbye through that lens, Westlake asks, "if this is not a homosexual relationship, what on earth is it?"16 The question resonates in his own work.

The section on homosexual subtext in Westlake’s essay.

Stark, R. (1962), The Hunter, p. 5

Stark, R. (1963), The Man With the Getaway Face, p. 119

Stark, R. (1966), The Seventh, p. 102

Stark, R. (1966), The Handle, p. 97

Stark, R. (1967), The Rare Coin Score, p. 115

Stark, R. (1967), The Green Eagle Score, p. 48

Stark, R. (1963), The Outfit, p. 168

Stark, R. (1964), The Score, p. 54

Stark, R. (1966), The Handle, p. 160

Stark, R. (1967), The Rare Coin Score, p. 3

Stark, R. (1966), The Handle, p. 49

Stark, R. (1969), The Sour Lemon Score, p. 109-110

Stark, R. (1969), The Sour Lemon Score, p. 51

Stark, R. (1974), Butcher’s Moon, p. 180

Westlake, D. (1984), ‘The Hardboiled Dicks’, The Getaway Car (2014)

Westlake, D. (1984), ‘The Hardboiled Dicks’, The Getaway Car (2014)